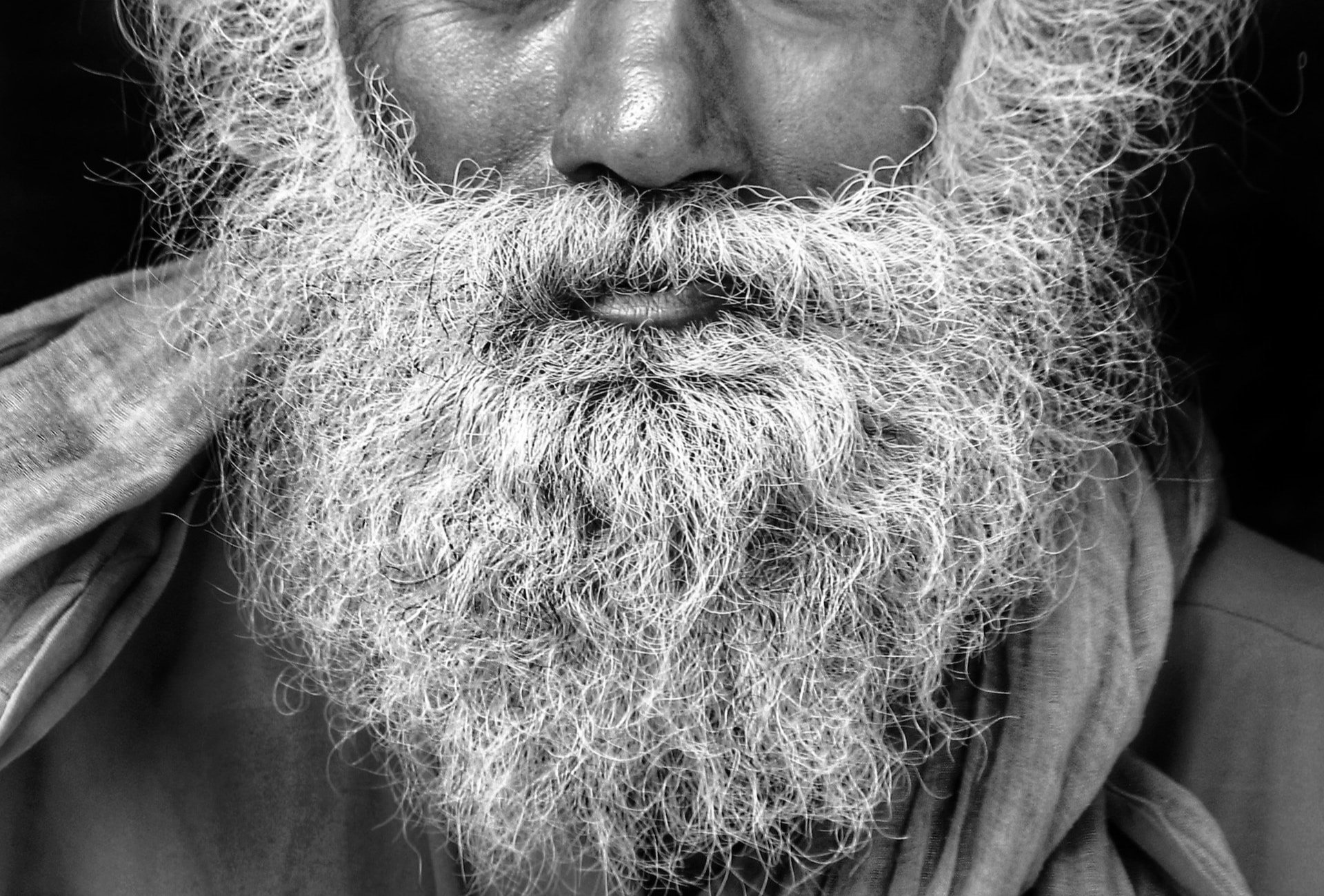

Hair: Marker of Manhood?

Photo by Dibakar Roy on Unsplash

I am reading Empireland: How Imperialism has Shaped Modern Britain by Sathnam Sanghera (2021, 2023). Sanghera was born in Britain, his family from India. Not surprisingly, he has a critical angle on the aggressive usurpation of wealth flowing to the British Empire from its several colonies, not least from India. Amid this quite sobering assessment Sanghera makes of the empire as ruthless looter, I came across a sentence in a footnote that struck me as hilarious. Background to the sentence: Lord Kitchener was a major player in the affairs of the Empire as a military leader, and a colonial administrator in Egypt and India. But for all his visibility and prominence as a major player in the Empire, we get this quite funny sentence about him:

In the twenty-first century, Kitchener is most famous for two things: his gimlet-eyed portrait on the Great War poster proclaiming, “Your country needs you,” and his extraordinary mustache (p. 50).

Imagine: for all of his prominent leadership, it is his mustache that lingers in memory. Sanghera comments further:

And such extravagant mustaches, also sported by Younghusband and Waddell, are arguably another legacy of empire. The historian Piers Brendon has argued that the mustache became an “emblem of empire” in the nineteenth century. Apparently, clean-shaven British soldiers in imperial India found themselves being glanced at with “amazement and contempt” by their bearded Indian counterparts because of their “(unmanly) countenances emasculated by the razor.” As they “could not afford to appear less masculine and aggressive than their Indian comrades in the Army,” they “had to assert the supremacy of the imperial race. So began what became known as the ‘the mustache movement’.” Soon the mustache was the sacred emblem of the imperialist. Back in Britain, the Edwardians saw the mustache as the preserve of the upper echelons of society—servants who tried to grow one were given the short shrift—and Brendon goes as far as asserting that there is a correlation between the prevalence of mustaches in public life and the vigor of empire, observing that the British commanding officer who in 1942 lost to the Japanese at Singapore, General Percival, “had a miserable apology of a mustache.”

In the belated empire the mustache became a marker of class distinction.

That verdict by Sanghera got me to thinking about “hair” as a male marker in the Bible. (The Bible never uses the term “mustache”). What follows is a commentary on “hair as social marker.”

1. There is a series of texts in which the marker of hair strikes one as odd and noticeable, until we recognize that hair as taken as evidence of maleness. Thus Jacob expresses his anxiety about his lack of hair to his mother, Rebecca:

Look, my brother Esau is a hairy man, and I am a man of smooth skin. Perhaps my father will feel me, and I shall seem to be mocking him, and bring a curse on myself and not a blessing (Genesis 27:11-12).

He feared that his smooth skin and lack of hair on his arms will offend his father, Isaac, who will curse him in his disappointment. Who wants a son who is not marked by manliness?!

Of course “hair” figures prominently in the Samson narrative. Samson in introduced into the narrative to be “a nazarite to God” from birth (Judges 13:5), so that “no razor is to come on his head” (Judges 13:5). In his rendezvous with Delilah, a Palestinian woman, she tried to find out the source of his immense strength. Three times he deceived her:

-He told her that, “If they bind me with seven fresh bows that are not dried out, then I shall become weak, and be like anyone else (v. 7).

-He told her “If they bind me with new ropes that have not been used, then I shall become weak, and be like anyone else (v. 11).

-He told her, “If you weave the seven locks of my head with the web make it tight with the pin, then I shall become weak, and be like anyone else” (v. 13).

Finally as she persists, Samson tells her the truth of his great strength:

A razor has never come on my head; for I have been a nazarite to God from my mother’s womb. If my head were shaved, then my strength would leave me; I would become weak, and be like anyone else (v. 17).

This time it is the truth: he was shaved and became weak and fell into the hands of the Philistines:

So the Philistines seized him and gouged out his eyes. They brought him down to Gaza and bound him with bronze shackles; and he ground at the mill in the prison (v. 21).

But the narrator adds, ominously:

But the hair of his head began to grow again after he had been shaved (v. 22).

With a burst of recovered strength Samson uses his recovered hair and recovered strength to work havoc on the Philistines:

And Samson grasped the two middle pillars on which the house rested, and he leaned his weight against them, his right hand on the one and his left hand on the other…He strained with all his might; and the house fell on the lords and all the people who were in it. So those he killed at his death were more than those he had killed during his life (vv. 29-30).

Samson’s story is one of hair—hair lost and hair restored. The story is framed in a pious way to preclude Samson’s hair from becoming a fetish. At the outset, Samson’s parents are portrayed as heeding divine guidance about their new son (13:3-23). At the end Samson finishes with a prayer of petition:

O Lord God, remember me and strengthen me only this once, O God, so that with this one act of revenge I may pay back the Philistines for my two eyes (v. 28).

Thus his hair is a vehicle for the power of God that is given him at birth, and then again in the instant of his death.

The narrator takes the trouble to attest to the luxurious growth of hair by Absalom:

Now in all Israel there was no one to be praised so much for his beauty as Absalom; from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head the was no blemish in him. When he cut the hair of his head (for at the end of every year he used to cut it; when it was heavy in him, he cut it), he weighted the hair of his head, two hundred shekels by the king’s weigh (II Samuel 14:25-26).

He was beautiful and the father of a beautiful daughter (v. 27). His hair indicated for the narrator that he is true son of David (see I Samuel 16:12), and surely qualified to be the next king in Israel after David. As the story unfolds, Absalom’s hair apparently did him in, as he was caught by the head in an oak tree and “left hanging between heaven and earth” (II Samuel 18:9). His detention, caught by the hair, made it easy for Joab and his men to execute him.

Finally we may notice an incidental note abut Elijah the prophet. We have, before II Kings 1, already witnessed Elijah’s immense authority and power. And now, in his last act, he defies the king with a sequence of mighty shows of his power. It is tersely noted that he is,

a hairy man, with a leather belt around his waist. He said, “It is Elijah the Tishbite (II Kings 1:8).

Nothing is made of his hair, though along with his leather belt he is portrayed as an “outsider.” Nevertheless we are left to imagine, if we want, that his uncommon power is linked to his hair. Thus we may add his name to the roster of those whose great hair yields a marker of virility. In his case his manly authority was in defiance of royal power.

It is clear enough that hair was in that ancient world an identifying marker as it was for Lord Kitchener later on in the Empire. In each case, the hair specifies power and authority. For Jacob, he worried that Esau’s hair would please his father, unlike his own smooth skin. Samson’s power is self-evident as is Absalom’s attractiveness. Elijah in his own context executes transformative power as well.

2. We may also notice narrative cases in which the loss of hair or lack of hair is portrayed as “de-manning” a man, reducing him to weakness, vulnerability, and helplessness. The most dramatic case is that of Samson. When Delilah finally learns the secret of his hair, she promptly cuts it off:

She let him fall asleep; and she called a man, and had him shave off the seven locks of his head (Judges 16:19).

He narrator adds laconically:

He began to weaken and his strength left him (v. 19).

He experienced a quick radical shift from “strength” to “weakness.” But then the narrator gives us a clue that his weakness could not last:

But the hair of his head began to grow again after it had been shaved (Judges 16:22).

His strength was fully restored, enough to have his narrative end in massive destruction:

So those he killed at his death were more than those he had killed during his life (v. 30).

The process whereby Delilah had de-manned Samson was not permanent. But it was costly and devastating during his run of “weakness.”

In II Samuel 10:4 we have only this brief note:

Hanun, king of the Ammonites, is persuaded that David’s envoys to him are in fact spies. In response to that supposed identification of the envoys,

Hanun seized David’s envoys, shaved off half the beard of each, cut off their garments in the middle of their hips and sent them away (II Samuel 10:4).

The note is terse. David’s initial response to the humiliating brutality against his men is one of concern for their manly dignity. He allows them time to recover their manliness:

Remain at Jericho until your beards have grown, and then return (v. 5).

But the humiliation of David and his men is so profound that it led to a bloody war that David wages against the Ammonites, and against their allies, the Arameans. The retaliation that David wrought against the Ammonites and the Arameans for the humiliation of his men is violent and vengeful:

David killed of the Arameans seven hundred chariot teams, and forty thousand horsemen, and wounded Shobach the commander of their army, so that he did there (v. 18).

The third case is not clearly pertinent to our theme, but surely worth a mention:

He [Elisha] went up from there to Bethel; and while he was going up on the way, some small boys came out of the city and jeered at him, saying, “Go away, baldhead! Go away, baldhead!” When he turned around and saw them, he cursed them in the name of the Lord. Then two she-bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the boys (II Kings 2:23-24).

There is no commentary on Elisha’s “baldness.” In any case he apparently lacked the beard of manly authorizing hair that even Elijah, his predecessor, was able to exhibit. Elisha’s response to the jeering boys was that he cursed them. And his curse was effective, indicating his capacity and authority to mobilize God, even if he had no good beard. The prophet is not to be mocked! He enjoys the protective support of the God to whom he bears witness.

Thus we may see a defining contrast between those with hair (Jacob, Samson, Absalom, Elijah) and those without hair (Samson again, David’s men, Elisha). The manly marker of hair is taken seriously in these narratives, as seriously as Lord Kitchener and the other imperial nabobs took their authorizing mustaches.

3. We may notice, beyond hair and no hair, a third group of texts wherein the hair of the vulnerable in society is counted, treasured and protected by a powerful guarantor. In this third usage, the threat to one’s hair or one’s head is taken as a threat to the person; thus the hair stands, synecdochically, for the whole of the person. The protection of one’s hair is the protection of the person. The “formula of protection” is reiterated in the following:

-Saul proposed to kill his son Jonathan; but the people rallied to protect Jonathan from his father:

“Shall Jonathan die, who has accomplished this great victory in Israel? Far from it! As the Lord lives, not one hair of his head shall fall to the ground; for he has worked with God today.” So the people ransomed Jonathan, and he did no die (I Samuel 14:45).

-David promises to protect the woman from Tekoa who had played a role in support of David and his son:

If anyone says anything to you, bring him to me, and he shall never touch you again…As the Lord lives, not one hair of your son shall fall to the ground (II Samuel 14:10-11).

-In the contest for kingship Solomon promises to protect Adonijah, his brother and rival for the throne:

If he proves to be a worthy man, not one of his hairs shall fall to the ground (I Kings 1:52).

Solomon’s vow of protection for Adonijah, however, is sharply qualified and conditional:

But if wickedness is found in him, he shall die.

Thus “hair” becomes a stand-in for the person whose life is in jeopardy.

-The formula is reiterated by Jesus as protection for his followers when they are in danger and under persecution:

But not a hair of your head will perish. By your endurance you will gain your souls (Luke 21:18-19).

Or in a variant:

But even the hairs of your head are counted. Do not be afraid; you are of more value than many sparrows (Luke 12:7; see Matthew 10:30).

Thus the formula is reiterated as an assurance of providential protection and oversight by God who will protect those who adhere to the new regime that Jesus has inaugurated.

Finally is the reiteration of this formula of protection, notice should be taken of its voicing in the first answer of the Heidelberg Catechism:

Question: What is your only comfort, in life and in death?

Answer: That I belong—body and soul, in life and in death—not to myself but to my faithful Savior Jesus Christ, who at the cost of his own blood has fully paid for all my sins and has completely freed me from the dominion of the devil; that he protects me so well that without the will of my Father in heaven not a hair can fall from my head; indeed, that everything must fit his purpose for my salvation. Therefore by his Holy Spirit, he also assures me of eternal life, and makes me wholeheartedly willing and ready from now on to live for him.

This eloquent response not only affirms redemption as the work of Christ; it affirms as well the on-going protective providence of the “Father” God. Thus the catechism generalizes a formula that heretofore had pertained in particular circumstances, so that it is now a general assurance of God’s protective governance. Insofar as the catechism is addressed to younger teen-agers, we might notice that the affirmation may serve to assuage the anxiety that frequently besets such teen-agers. Thus beyond the hairy men filled with power and authority, and beyond the un-manned who are left hairless, God is mobilized to protect those whose hair (whose lives) are at risk. We may imagine the preening nabobs of the empire, alongside Lord Kitchener, with much time before the mirror, making sure that every hair of the mustache is in proper position to exude power and authority. The problem with such preening before the mirror is that one cannot see or notice the neighbor.

Before we finish this exposition concerning hair, we may pay attention to the fact that the gospel does not linger over hair, but has a very different notion of the markers of humanity. Thus already in the narrative of I Samuel 16:1-13 (where the narrator reports that the young David was “ruddy and had beautiful eyes, and was handsome,” v. 12) the Lord has a different criterion from the one to which old Samuel was attracted:

But the Lord said to Samuel, “Do not look on his appearance or on the height of his stature, because I have rejected him; for the Lord does not see as mortals see; they look on outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart (I Samuel 16:7).

The matter is reiterated by Paul:

We are not commending ourselves to you again, but giving you an opportunity to boast about us, so that you may be able to answer those who boast in outward appearance and not in the heart (II Corinthians 5:12).

Paul offers an alternative to assessments by “outward appearance”:

From now on, therefore, we regard no one from a human point of view; even though we once knew Christ from a human point of view, we know him no longer in that way (II Corinthians 5:16).

In both I Samuel 16:1-13 and II Corinthians 5:12-16 those who stand in the gospel are called away from the attractions of appearance—hair, mustache, and all! The alternative is to pay attention the human heart, the organ through which we may love God (with all our heart”!), and the organ through which we may notice, love, and stand in solidarity with neighbors, many of whom are “marred…beyond human semblance” (Isaiah 52:14). Almost at random I suggest that the counsel of the apostle is a reliable guide:

Do not adorn yourselves outwardly by braiding your hair, and by wearing gold ornaments or fine clothing; rather, let your adornment be the inner self with the lasting beauty of a gentle and quiet spirit, which is very precious in God’s sight (I Peter 3:3-4).

The beauty of the human person is not in braided hair. It is in a gentle spirit. The apostle explicates that gentle spirit:

Finally, all of you, have unity of spirit, sympathy, love for one another, a tender heart, and a humble mind. Do not repay evil for evil or abuse for abuse; but, on the contrary, repay with a blessing (vv. 8-9).

We have before us a clear either/or. The posturing of an imperial mustache (hair-do) before the mirror, or a life propelled by a responsive heart. The church has a huge stake in refusing and resisting the manly images of our society. Judging from all our ads for hair, facial care, and shaving products, Lord Kitchener has a great contemporary following. As always, the gospel summons is otherwise. The “otherwise” is neighborliness that has little time for posturing mirrors. It is this otherwise that permits us to see the wellbeing of the human community (and of all creatures) as the intent of the creator God.