Blog Posts

The Church and the Great Resignation

There’s a phenomenon we’re experiencing right now, one that is predicted to continue over the next year, called “The Great Resignation.” (If you haven’t heard about it yet, you can read about it HERE or HERE.)

4 million people in the U.S. quit their jobs in April alone, and a not insignificant number of others are at least considering it.

In early August, CNBC reported a survey which showed that:

38% of US workers are seeking employment elsewhere.

41% are considering leaving their current job within the next six months.

52% of people who are thinking about quitting say they're financially prepared to do so

57% of people who say they are not financially prepared to do so are willing to take on debt while they search for their next job.

There is something happening, as people begin to examine the ways life has changed over the last year and a half.

We are, collectively, holding up the pieces of our lives and asking what parts we want to keep and what parts we can let go of. We are asking questions about what really matters.

On a somewhat smaller scale than the job market, but no less impactful for those of us in church leadership, people are doing this same thing with their faith. People are pondering what to keep and what to let go of.

And, friends in the church, it’s time for us to be honest about which one of those most people are choosing.

Over the past few weeks, I have had many conversations about how the church “doesn’t mean what it used to mean to me” and how faith is being found more outside of the church than inside. Just as they are doing with their work and their lives at home, our people are holding up the pieces of their life of faith and asking what really matters.

This is, dare I say it, the beautiful, glorious, and God-centered work of deconstruction.

This term has received quite a bit of negative press lately as churches blame the decrease in worship attendance on a loss of faith, instead of what it really is, people deciding that their faith does not need the church.

Add to this the fact that many church workers, pastors, music directors, youth leaders, and other church staff have all at least considered leaving ministry, if not currently planning to do so. All of that on top of the decrease in seminary students and an increase in retiring clergy and you have the recipe for a very different future church than we are currently planning for.

The church has some very challenging and vulnerable work to do. Together. Denominational leaders and staff and clergy and congregations. I call it vulnerable work because it’s so hard to come face to face with difficult truths, the primary one being that the way we have always done it isn’t going to work where we are going next.

This feeling of vulnerability can either create space for the spirit to create and move and grow or it can cause us to harden and dig our heels in and the new life we are being asked to plant and care for will not be able to take root.

I don’t have the answers, not at all, but I can tell you with complete confidence that riding the pendulum swing back to “how we used to do it” is a recipe for the death of the future church. And while I don’t have answers, I do have some ideas and questions, based on the interactions I have with my community of faithful non-churchgoers whom I pastor weekly through the airwaves of a podcast.

To my clergy colleagues, our people are as tired and struggling with their faith as much as we are.

Your vulnerability and honesty about these struggles from the pulpit are needed.

The church should be a place where we can do this struggle together, not a place where struggling doubters feel they cannot go. I know how tired you are. Does your congregation?

To the higher-ups across denominations, do you know how close your clergy are to leaving ministry right now? They need you to see them, hear them, and advocate for them, and they need you to be at the forefront of thinking creatively about the future of the church.

To people of faith in and outside of congregations, keep asking questions. Keep struggling and doubting and wondering and dreaming.

You are imagining the future we keep talking about.

Natalia Terfa

Natalia is a Lutheran pastor and author who lives in Minneapolis with her hubby, kiddo, and kitty babies. She loves to bake, to read, practice yoga, and find nature adventures. She is passionate about the church of the future, one with no boundaries and filled to the brim with love and grace and laughter and snark and a lot of fellow “not that kind of Christians.”

Natalia co-hosts Cafeteria Christian, a podcast for people who love Jesus but aren’t so sure about his followers.

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

ABC Prayer

As if the ordinary transition back-to-school after summer were not hectic enough, this year parents are confronting a return to school in the shadow of the Delta variant of the deadly COVID-19 virus, a variant that has increased numbers of infections among children.

For many American parents, our kids aren’t even eligible yet for COVID vaccines (the youngest currently eligible are 12), and some of us are confronting sending kids to schools that are not requiring masks or distancing.

Rightly, this prospect feels alternately terrifying and impossible. And at the same time, the rhythms of childhood are pulsing as normal: did we get school supplies? Have you gotten your teacher assignment? Am I ever going to be able to complete an interruption-free workday again? Am I eternally consigned to meal, cleanup, and laundry duty until the end of time?

In this article I do not have answers or public health expert-level advice. For that I would suggest turning to reliable news sources and also consulting with your local pediatrician. I’d also recommend that all eligible people get vaccinated, and that parents protect their own children and others by wearing masks and staying home from school when ill.

What I do want to offer today, though, is a prayer — for all of us, parents, caregivers, students, teachers, administrators, supporters alike, listed in the form of the ABCs. May God go before us even into this uncertainty, fear, and frustration.

Dear God, Today I pray for all of us as a new school year begins:

A is for aptitude. May each student recognize their own ability and aptitude to learn and grow, and embrace an environment dedicated to learning.

B is for boxes. While we are checking the boxes of all the things we need to do before school starts, may we look up and see one another - and prioritize kindness over lists.

C is for cereal. Thank you God for colorful, easy breakfasts - and bless the hands that prepare our students’ breakfasts.

D is for dessert. May we all make time to share in unnecessary moments of joy in the midst of a long day.

E is for excitement. May we never be too old to share in a child’s excitement for learning.

F is for friends. In the midst of a global pandemic, may God bless children’s friendships — and help the adults in their lives to show them how to be caring, considerate, and humble friends.

G is for grace. We are all stressed, angry, and frustrated for good reason. May we treat one another with grace and offer forgiveness whenever possible.

H is for help. May parents, teachers, students and administrators see themselves as helping one another, and not as adversaries.

I is for imagination. We need new imagination to see our way out of this crisis. May our schools be filled with kind and imaginative thinkers, and may teachers be given the space to foster imagination.

J is for jokes. May we all make room for healing laughter.

K is for kindness. May our kids bring kindness with them as they enter the school building, and may they be met with kindness from others.

L is for llamas. May we remember the gift of learning about animals, and that this earth is not only ours, but also the home to plants and animals.

M is for maps. As students learn about the vastness of the world, may they develop empathy for all of God’s people.

N is for No. Sometimes the answer is No. No, your right not to wear a mask does not supersede the school’s right to create a safe environment for learning.

O is for outside. May students attend schools with safe and accessible outdoor space to learn through play.

P is for play. May students play together and teach one another about creativity and patience.

Q is for quit. Sometimes it’s OK to quit. May we teach discernment and flexibility to our children.

R is for red. I pray for all the colorful artwork that students will make in school this year, and may it help them appreciate the beauty of the world all around them, and the beauty inside themselves.

S is for smart. May students learn that being smart takes dedication, patience, and listening to others — and knowing that there is much they do not know.

T is for teachers. May we honor our teachers.

U is for umbrellas. May students have access to all the gear they need to get to and from school safely.

V is for violence. May we support our schools and students in their efforts to combat gun violence, and may we do our part to support non-violence in our homes.

W is for water. After a season of devastating drought in many areas, may we teach our students how to conserve and appreciate access to water.

X is for X-cellent. May we prioritize excellence in grace, kindness, and truth.

Y is for you. That you may know that God is watching over you and your family as you prepare for the school year ahead.

Z is for Zoom. May we see the ways God has blessed our schools, students and families over the past two years — even in unexpected ways — and trust that God’s providence will continue to guide our children, our teachers, and ourselves.

AMEN.

Angela Denker

Angela Denker, author of Red State Christians: Understanding the Voters who elected Donald Trump (Fortress: August 2019), is a Lutheran Pastor and veteran journalist who has written for Sports Illustrated, The Washington Post, Christian Century, and Christianity Today. She has pastored congregations in Las Vegas, Chicago, Orange County (Calif.), the Twin Cities, and rural Minnesota.

Twitter | @angela_denker

Facebook | @angeladenker1

Blog | http://agoodchristianwoman.blogspot.com

Website | https://www.angeladenker.com

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

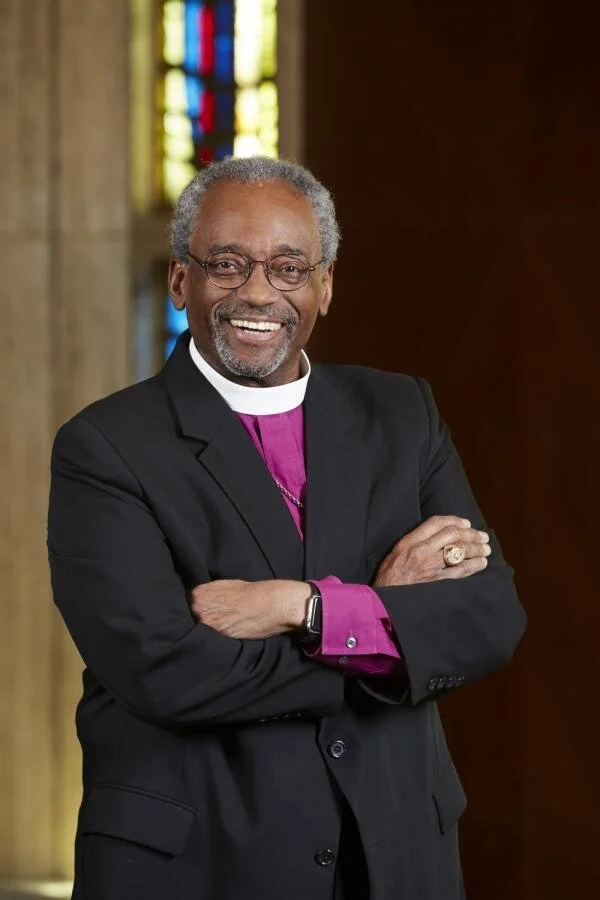

Encouraging Americans to get vaccinated: "Do this one for the children"

Join Presiding Bishop Michael Curry @PB_Curry by sharing your own “I Got Mine” story. Post your photo or video with the #igotmine hashtag, tag and invite your friends, and tell the world what getting the COVID-19 vaccine means to you.

I’m Michael Curry, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church. When I was in elementary school, I came home one day and my father asked me if I got my sugar cube. And I at first didn’t know what he was talking about.

And then remembered earlier that day, we had been given a little sugar cube — this is back in the 1960s — with some medicine or something that was on it. And I ate it and took it and we all got it. It was the polio vaccine.

Years later, while I didn’t know why my father always walked with a limp, my Aunt Carrie told me that the reason he walked with a limp was because he had polio when he was a little boy. And I realized why he was so thankful that his child was able to get the polio vaccine.

Vaccines can help us save lives and make life livable.

We have the opportunity to get that vaccine now for this COVID-19. I got mine, we get can get ours. For ourselves — and if not for ourselves — for our children who still don’t have a vaccine yet.

I got the polio vaccine as a little child. Right now, adults can get the Covid vaccine to help protect our children. That’s what the Bible means when Jesus says, “you shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

COVID-19 Vaccine Toolkit (via @iamepiscopalian): https://t.co/u5HnH41VaF

The #COVIDVaccine saves lives. #igotmine to do my part to live out the Bible’s commandment to “Love your neighbor as yourself.” And I’m inviting my friends to share their own #igotmine stories.

See related op-ed in USA Today.

Shared with with permission by the Office of the Right Reverend Michael B. Curry, The Episcopal Church, in its entirety. The Most Rev. Michael Curry is the presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church and the author of the book "Love Is the Way: Holding On to Hope in Troubling Times".

Bishop Michael Curry

The Most Rev. Michael B. Curry is Presiding Bishop and Primate of The Episcopal Church. He is the Chief Pastor and serves as President and Chief Executive Officer, and as Chair of the Executive Council of The Episcopal Church.

Facebook | @PBMBCurry

Twitter | @BishopCurry

Twitter | @episcopalchurch

Facebook | @episcopalian

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

The Future of the Church is Young

A few weeks ago I went on a mission trip with a group of middle schoolers from my church. I’ve led middle schoolers in different capacities over the years, but nowadays I spend most of my time with elementary kids. Honestly, I had forgotten how wonderful and absolutely absurd middle schoolers can be. I truly enjoyed my time with our students, I learned a lot from them and was challenged by my time with them. Yes, they tested my patience in more ways than one (they’re really good at it), but to my surprise they challenged the way I had been thinking about them as members of our church community. Throughout the trip, they had a lot of opportunities to be honest about their faith and their experiences in the church — a beautiful element of mission trips that I had forgotten about.

I’m still processing all that has stirred in me since our trip, but as always, I’d like to share my experiences and what questions I’m sitting with.

Open Mic

One of our evening outings was to an open mic prayer worship service which may be familiar to some but was not familiar to our middle schoolers. The pastor opened up the service by explaining how anyone could come up at any time to share a prayer or a piece of scripture that was on their heart. The worship team would be singing, members would be praying, reading scripture, and leaving space for anybody to forward as they felt called to do so. For the first hour most of the people who stepped forward were members of the worshiping community. Finally the pastor got up to encourage the students to share something, anything and with that prompt one brave soul decided to step forward.

Bashfully stepping to the mic, the kid began pouring out their heart. They talked about how their mom had been struggling financially and how that struggle has stolen their joy, impacted their family dynamics, and how everyone is really feeling the pressure, pain, and sadness of their financial situation. After sharing this story, a member of this worshiping community got up and together we prayed for the student’s family.

Then the floodgates were opened and student after student got up to ask for prayer as they shared about their difficult home lives like; upcoming life or death surgeries, cancer, suicide, financial insecurities, and family dysfunction.

They truly bore their burdens before the community.

As I listened to all of the sixth, seventh, and eighth grade students speak, my heart broke, and I was pushed to look at them differently. I had spent the first few days caught up in all of their minor annoyances, keeping up with the schedule, and making sure that at the very least their Bibles were in their backpacks.

At some point, I confess, I had begun to think that their hardships and problems were rather shallow.

Of course I had thought about the impact of the pandemic, and then I started to compare that to the hardships of some adults I know who have “real” responsibilities and “real” problems. What? As if these middle schoolers are not real people with hearts that feel and eyes that see and minds that are trying to process all that surrounds them.

Listen, our kids feel the weight of this world too.

They may or may not be paying bills, but they are seeing and feeling the burden of financial insecurities. They’re feeling the weight of family dysfunction whether it’s alcoholism, abuse, the process of divorce, or otherwise; they see it and they feel it, for themselves and those around them.

Later that evening we had time with our church group to sit and talk about their experiences at the prayer service. I must admit, the students were not afraid to share how boring they thought our own worshiping community was, which was no surprise to me but it did spark a helpful conversation about what they hope for and desire in their own communities.

They want a community that feels genuine, personable and open. What a beautiful thing to want for your community. This is what I've learned, my students desire for the church to feel like a welcoming place for them; a place where the “mic is open” and they have the welcomed authority to co-lead.

I’m not talking about “youth Sunday” where once a year they get to lead worship however they want. I’m not talking about all the opportunities they have to “serve” and do the heavy lifting in the projects no one else wants. No, these students enjoyed the freedom to be a part of the community, like the “grown ups” and not apart from the community as the youth group.

So the question is, what does it look like for the voices of our youth to be invited in, heard and included in the ways we do for adults? What needs adjusting in our minds and hearts to see and hear them as members?

R.E.S.P.E.C.T. Please

Part of our mission work throughout the week was going to different service sites across the city. Students are asked to work on a variety of projects with a variety of people. At the end of our service day, we gave the students an opportunity to ask the adults some questions. One question that continues to stick in my mind was, “Why do adults always look down on kids?”

While there were chuckles from the adults, myself included, I immediately felt the genuine heartbreak in this question. I began thinking about all of the hard work that our students had done all day and all week. I started to realize how we kept asking and asking of them. We had asked them to pick up trash around neighborhoods, pull giant weeds in gardens, pack food at pantries, and make friends with every person they met. Yes, they’re on a mission trip and that’s part of the gig.

But the truth is that we have asked for and expected a lot from these kids. We want them to behave a certain way in church, be excited about youth ministry but not too excited that they cause a ruckus. They’re “what’s wrong with the church” and they’re usually the first to get volun-told for projects at church. This question gave the group an opportunity to be honest about the fact that adults are complicated beings too. We don’t always get things right and we are coming to the table with our own stories and our own desires.

Our students want to be respected in the ways that every being deserves.

Some of us have a tendency to think that respect needs to be earned; that might make sense sometimes. But here, in our faith community? With the youth of our community? I think they have asked a great question. I continue to ask myself, how do we teach, nurture, and encourage other generations while respecting them as individuals and a collective?

Can we…?

I’ve continued to mull over one of our final conversations. We are driving a bunch of minivans and there are seven middle schoolers in my van, having a wonderful time, bopping to classic cartoon theme songs. We are laughing, joking, and chatting when there just so happened to a prime opportunity to ask them a question about confirmation.

I asked them “If you were in charge of student programming, (what we call confirmation) what would you do? What would it look like? I got a few less than helpful comments and never-going-to-happen suggestions, but I also got a lot of really constructive feedback. There was more excitement about their ideas and the possibilities than I was anticipating.

Most profoundly, they asked for an opportunity to disciple others.

They literally asked me if they could help teach the elementary kids about Jesus.

“You know what we should do? Like, we should have one Wednesday or Sunday where we all get to lead the elementary kids or something? Play games, do the skits and bible study and stuff. That would be so fun! And it would help us learn to share what we’ve learned!”

I am beside myself every time I think about that request. They want to go and make disciples. Had I not asked, I would have not known. If I gave them more opportunities to imagine “the Church,” they would.

I am sharing these experiences with you because they brought me more understanding, empathy, and encouragement. As we continue to walk into a new chapter in the Church I want us to be doing so wisely. We’re wondering, what does our community need, how do we serve each other well? That requires a lens that looks for the underserved, under-appreciated, and unheard; in many of our communities that includes the youth. After a week with these rowdy kids, I feel challenged to look at the ways I embrace and engage our youth and how I can be a better advocate for them within our community.

I embolden you to consider to do the same.

Jessica Gulseth

Jess Gulseth is a seminarian at Luther Seminary in St. Paul seeking ordination in the ELCA. Jess is a Director of Children & Family ministry in the Des Moines, IA area.

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

A God Who Cares? A Meditation on John 11:32-37

When Mary came where Jesus was and saw him, she knelt at his feet and said to him, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.” When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. He said, “Where have you laid him?” They said to him, “Lord, come and see.” Jesus began to weep. So the Jews said, “See how he loved him!” But some of them said, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?” (John 11:32-37)

In times of great pain, both global and personal, I often find myself returning again and again to these verses from John 11. The image of my Savior, weakened, weeping and disturbed, is so unworldly and unexpected that it draws me near again and again, and I remember that the God I worship is so very different than the god the world idolizes.

Just before Jesus goes to Bethany to see his dead friend Lazarus, he is threatened at a religious festival: accused and nearly stoned and arrested. He escapes, barely, with his life, and then goes alone across the river Jordan, where many believed in him.

Jesus’ life, like my own and I suspect yours as well, is an ongoing, twisting and turning road filled with ups and downs, triumphs and failures, love and hate, joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain. At times Jesus was revered and beloved; at other times those he trusted accused him falsely and told lies about him. They claimed the truths he held most central to his life were not true at all.

This mix of circumstances and relationships is of course the sum of the human condition: what it means to be human.

The absence of pain or sorrow or compassion would mean you were no longer what God created you to be.

And yet in response to a world filled with such dynamic change and pain, it is tempting to respond with an increasing callousness and feigned indifference. To live each day in 2021 America is a practice in becoming insensate to an another’s suffering.

I woke up this week to smoky skies, burning eyes and a stuffed-up nose. My own discomfort and air quality alert meant thousands of acres burning in the West. It meant firefighters risking their lives. It meant children and grandparents losing their homes.

Was it my gas-guzzling car? My haphazard tossing of items into recycling that would never be recycled after all? My fast-fashion purchases?

I watch videos of flooded roads and streams in Germany and China this week.

I see a group of women at the park in my neighborhood wearing layers of clothing and carrying backpacks and trash bags filled with their belongings. I bike ride past an encampment of tents near the lake. I read that my sons’ school district was dropping off iPads at those tents for students to attend online summer school, and I try to imagine sitting with my children in 98 degree heat and studying a lesson.

I stare at charts and graphs of COVID-19’s impact on my city, my state, my country, our world. Have you read the study that says that the larger the number of deaths, the less of an impact it registers on people reading the report?

We can grasp the individual stories and suffering of 12 people killed in a multi-car accident, or, tragically, a mass shooting. We can read CaringBridge and dwell in the pain and tragedy of a single case of cancer among our loved ones. But hundreds of thousands; millions dead: it is a blip.

Perhaps you are like me and you have read lots of obituaries in the past 16 months. Sometimes maybe you read them stealthily, looking for ways in which the dead person was unlike you or your family, so that you could still believe that you were safe; so that I could still believe I was safe.

In the modern world, we have to build walls between ourselves; imagine reasons why another’s suffering was their fault.

This is the capitalist, objectivist, libertarian, Ayn Randian dream: that you can get yourself to a place where you are unfettered by another’s pain or suffering; where all that matters is you and your productivity and perhaps, your happiness. Maybe this would work if you did not have parents or siblings or children or friends, but what kind of life would that be?

I want to encourage each of you, right now, to make a proud admission.

“I CARE.”

To admit that you care is to admit your own powerlessness and fallibility. To admit that you care is to open yourself to sadness and pain, to hearing places where you have previously failed, to admit that you are inextricably tied even to the person you disdain because, at root, humanity is a we.

This is what Jesus demonstrated so powerfully when he came to Lazarus’ tomb.

If we focus only on the resurrection we miss the moment just before it, that moment that made resurrection and ultimately eternal life possible. It was the caring: the admission that another person’s suffering causes God pain.

Jesus wept.

He was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. Jesus was emotional. He was beside himself. He was wracked by sobs. He was inconsolable. Jesus wept as those beside him wept. Their tears brought him to tears. He was not stoic. He did not stand strongly and wipe away another’s tears. Instead, Jesus let his own tears fall down his face, in the sight of all assembled.

It was then that his power came to him. New life was possible for Lazarus because God cared about human suffering.

When I miss this story about Jesus, I miss it all.

And so I will tell you honestly that this week I have wept. I have been greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved by so much suffering and death and pain, close to home and far away. I have wished that I didn’t care so much. I have known that it is only the caring that saves me.

Angela Denker

Angela Denker, author of Red State Christians: Understanding the Voters who elected Donald Trump (Fortress: August 2019), is a Lutheran Pastor and veteran journalist who has written for Sports Illustrated, The Washington Post, Christian Century, and Christianity Today. She has pastored congregations in Las Vegas, Chicago, Orange County (Calif.), the Twin Cities, and rural Minnesota.

Twitter | @angela_denker

Facebook | @angeladenker1

Blog | http://agoodchristianwoman.blogspot.com

Website | https://www.angeladenker.com

August 26, 2021

In a short-form, intentionally crafted gathering, you will encounter distinct voices, speaking from their own communities, enfleshing witness for this moment of challenge and creativity in the church and in the world. Between these witnesses, you will encounter liturgical experiments and collaborations to help digest the call of the divine.

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

AOC the Bible Teacher and Christian Nationalism

Last week Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez received over 250,000 Twitter likes for this little gem.

Using the now-common “Tell me without telling me meme,” Ocasio-Cortez scored a social media victory over her nemesis, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene. I, um, LOLed.

Social media memes won’t save democracy, and they won’t redeem the church.

But AOC, as she’s called, made a powerful point about how we use the Bible in the United States. Marjorie Taylor Greene poses as a champion of evangelical Christianity, and she advanced a theological point: God would not create a harmful disease. The point is misguided on at least two grounds. For one thing Covid-19 is just one of many awful diseases in the world, very few of which humans created in laboratories. For another the Bible quite clearly attributes some plagues to God, most notably in the Exodus story. The Congresswoman’s theological claim ran far ahead of her Bible knowledge.

There’s a warning for all of us here: there’s danger in using the Bible without listening to it. We’re all prone to do it, progressives and traditionalists alike. We use “Do not judge, so that you may not be judged” as an excuse to avoid moral discernment (Matthew 7:1). We call ourselves ‘Matthew 25 Christians’ — “I was hungry, and you fed me” — and we don’t much care if Jesus was talking about something other than acts of mercy. We cite passages about vulnerable aliens and strangers as if the Bible did not include passages like Ezra’s demand that the men of Judah divorce their non-Israelite wives. We’re not at our best when we reduce the Bible to a tool.

“Fundamentalists use the Bible like a drunk uses a lamppost — for support, but rarely for illumination.”

Unfortunately, this quote does not derive from the twentieth century preacher Harry Emerson Fosdick, as I was told. Instead, it originally applied to statistics: first we make up our minds, then we pick the data we like. I wish Fosdick had said it, though, because it truly does capture a powerful threat to American spiritual and social health: Christian nationalism.

Christian nationalism is the idea that God holds the United States in special regard. The nation was founded upon a Christian foundation, so the story goes, even a biblical one. That is why is has prospered so. Christian nationalism also holds that Americans have special virtues. So long as America does God’s will, God will bless our nation. Therefore, Christians should see to it that they elect officials who will enact a Christian, specifically a biblical, agenda. Christian people, institutions, and values should be privileged in American society.

Christian nationalism often expresses itself by blurring Christian and patriotic symbols. Church sanctuaries should have American flags, congregations should honor patriotic holidays, society should celebrate Christmas but not necessarily Jewish or Muslim holidays, and public schools should include prayer and Bible study. When Judge Roy Moore installed a display of the Ten Commandments in the Alabama Supreme Court, he demonstrated Christian nationalism.

There are lots of things to say about Christian nationalism, but recent research shows that the movement is not particularly about the gospel. There’s not much talk about Jesus and his teaching, but there’s lots of chatter about prayer in schools, the status of religious symbols and holidays, and other displays of civic piety. Preachers might appeal to Romans 13 (submit to the authorities), to the Bible’s military imagery, to the modern state of Israel, and to the “clobber passages” commonly deployed against sexual minorities.

Public crosses, yes; carrying one’s cross, not so much. That’s because Christian nationalism is about social privilege for certain kinds of White Christians, about a particular ordering of society, rather than loving one’s neighbor.

In Christian nationalism “Christianity” stands-in for other values. The sociologists Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry have pored over survey data to reveal important ways that Christian nationalism operates independently of Christian practice. Conventional measures of Christian religiosity often pull against folks’ adherence to Christian nationalism. According to Whitehead and Perry:

As Americans show greater agreement with Christian nationalism, they are more likely to view Muslim refugees as terrorist threats, agree that citizens should be made to show respect for America’s traditions, and oppose stricter gun laws. But as Americans become more religious in terms of attendance, prayer, and Scripture reading, they move in the opposite direction on these [and other] issues.

According to this research Christian nationalism is “more of an ethnic Christian-ism” than a theologically conservative Christianity. It tends to correlate with racist and antisemitic attitudes, valuing nativism and whiteness above inclusivity. It is also authoritarian valuing the interests of “folks like us” over representative democracy. The Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection is totally consistent with Christian nationalism: if “our” candidate doesn’t win, it’s time to adopt other, non-democratic, means. Those include recourse to violence.

In the context of Christian nationalism, it makes total sense for a politician to use the Bible without reading it.

In Christian nationalism the Bible is a source of authority rather than one of inspiration or instruction. In that world it’s a good thing to put your hand on a Bible when you’re sworn into office, but it’s a bad thing to read passages that might be inconvenient for the agenda.

During last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests in Washington, D.C., former President Donald Trump marched over to a local Episcopal church, took a Bible that was not his own, and held it upside down for the cameras. That scene dramatized the Bible’s role in Christian nationalism — not an inspiration, certainly not a guide, but a symbol of identity and belonging.

I visit lots of churches, sometimes to talk about controversial issues like human sexuality and immigration. Over the years one thing has become clear to me: congregations generally rush to debate the Bible’s significance for our concerns before they’ve ever had serious conversations about how the Bible forms our moral imaginations. That makes me sad. In our churches we need to devote serious energy to the process of modelling deliberate, healthy biblical interpretation.

In that way we might avoid the impression that we’re using the Bible without having read it.

Greg Carey

Greg Carey is Professor of New Testament at Lancaster Theological Seminary and an active layperson in the United Church of Christ. His books include studies of apocalyptic literature, the parables, the Gospel of Luke, and the ethics of biblical interpretation. His most recent books are Stories Jesus Told: How to Read a Parable and Using Our Outside Voice: Public Biblical Interpretation. In addition to serving on multiple editorial boards, Greg chairs the Professional Conduct Committee of the Society of Biblical Literature and serves on the Leadership Team of the Open and Affirming Coalition of the United Church of Christ.

Facebook | @gregc666

Twitter | @Greg_Carey

Facebook | @LancasterTheologicalSeminary

Twitter | @LancSem

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

God, Our Father: A Meditation for Father’s Day 2021

Each day before meals or bed, my 5-year-old son, when called upon to pray, recites a simple prayer he learned during a short-lived stint at an Evangelical preschool:

God our Father … God our Father …

The prayer is simple and short, and every time I hear him pray it, I am simultaneously so grateful that my 5-year-old knows how to pray, and also chiding myself that I should teach him that God is not exclusively male.

Such are the complications of an over-studied faith life.

Whatever my own misgivings about how popular culture continues to depict God, the truth is that God as Father remains the most predominant motif for God in American Christianity - and beyond. Many a camp counselor or worship leader has begun a prayer in this way: Father God … we just …

Almost every Sunday, church leaders across America begin worship with an invocation: in the name of the Father …

I wonder this year, as Father’s Day 2021 emerges out of the shadow of a global pandemic and national unrest, reckoning with racism and ongoing sexual abuse crises in the American church, if we should begin not by dismantling the language or gender of the Trinity itself but simply by reclaiming what it means that the masculinity of God is defined by the relational role of Father, and not by the cowboy, gun-toting masculinity popularized by many an American Christian leader or politician.

I’ve been thinking about this idea this week as Father’s Day approaches, because I’ve noticed a certain discrepancy in how the American Church approaches Mother’s Day and Father’s Day. Each year that I’ve spent in pastoral ministry, coming up on 10, I’ve been inundated by a horde of think-pieces and conversations about how the church ought to approach the secular holiday of Mother’s Day.

Some churches overdo: with chrysanthemums and applause and photo booths; other churches decide not to mention mothers at all. There is important and needed conversation about approaching Mother’s Day in church for all women: those struggling with infertility, those who are childless by choice; those who have recently lost their mothers; those who have a complicated or difficult relationship with their mothers.

As a mom myself, almost coming up on 10 years as well, even I found it a little bit exhausting. There didn’t seem to be a right way to do Mother’s Day in the church. Every approach seemed over-studied and under-practiced. I did my best to pray an inclusive prayer this year and left it at that.

Now, it is just a few days before Father’s Day, and I’ve heard almost nothing about how churches and church leaders plan to address Father’s Day in the church, save for perhaps singing Chris Tomlin’s Good, Good Father, if your worship is led by guitars; or Faith of Our Fathers; if you rely on an organ. There is no hand-wringing about honoring fathers but leaving out men who aren’t dads, by circumstance or by choice. There is no exchange of prayers and litanies, or discussions about how much or how little to honor dads on Father’s Day.

What little conversation there is about Father’s Day too often seems limited to beer and barbecue, if the cards I saw at Trader Joe’s are any indication. And this in itself is a sad commentary, for the ways it isolates and ignores the reality of alcoholism among American dads and families.

This vast discrepancy between over-conversation in the church regarding Mother’s Day and utter silence on Father’s Day reveals to me the very different ways that men and women have their identity constructed in much of American Christianity and American culture in general.

Women are almost always identified relationally: by our roles and relationships to others. We are valued for being kind, considerate, communicative and cooperative. In the church, we are too often viewed as analogous to Mary, the mother of Jesus. Motherhood has been called a Christian woman’s greatest calling, which does a great disservice to the broad and long history of female prophets, preachers and teachers, many of whom were never married.

For American Christian men, on the other hand, identity is constructed individually. The cult of rugged individualism does its greatest disservice to American men, who are encouraged to aspire to be the “strong, silent type.” After all, “there’s no crying in baseball.” The ideal American man needs nothing but his muscles, his pick-up truck, and his guns. If he is defined relationally, it is of a hierarchical sort, where he is the head of his wife and his children and his house, rather than coexisting in a symbiotic relationship.

Here’s where we must consider God the Father, however.

The idea that the Christian God has always been defined only in relationship strikes a mortal wound to the idea that the ideal Christian man must be an island, entire of himself.

After all, defining God predominately as God the Father means that the God who Christians worship is defined by God’s relationships, and as such, can exist only in relationship to God the Son and God the Holy Spirit: God in three persons, blessed Trinity.

What does this all have to do with Father’s Day in the church? Well, I’m not suggesting pinning flowers to the breast of each man in attendance, though it might be a fun idea and a good photo op. Instead, what I am suggesting first for American churches and church leaders is to simply imagine the transformative power of a witness for American masculinity that is rooted in relationship and family. Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 11 notwithstanding (and these words in context depict a familial mutuality rather than hierarchical headship), the Biblical view of fatherhood is one of quiet gentleness, forgiveness, and strength rooted in what often appears to be weakness.

This Father’s Day, if you think about or pray about or preach about fatherhood in your church, I encourage you to wonder about how differently Americans might view God if we constructed an image of God based on the father of the Prodigal Son, one of Jesus’ most powerful parables.

This father gave freely to his son what he had not earned, and then after his son abandoned him and his work, when the son returned to his father, contrite and penniless, his father did not kick him when he was down, demand restitution with interest, or spew hateful words about freeloaders and those who do not work hard enough. Instead, this gentle, forgiving, and relational father instantly forgives his son, and throws him a welcome party. Because more important than his money or his honor, this father, acting in the image of God the Father, valued love, and the dignity of each individual human life in relationship to his own.

Angela Denker

Angela Denker, author of Red State Christians: Understanding the Voters who elected Donald Trump (Fortress: August 2019), is a Lutheran Pastor and veteran journalist who has written for Sports Illustrated, The Washington Post, Christian Century, and Christianity Today. She has pastored congregations in Las Vegas, Chicago, Orange County (Calif.), the Twin Cities, and rural Minnesota.

Twitter | @angela_denker

Facebook | @angeladenker1

Blog | http://agoodchristianwoman.blogspot.com

Website | https://www.angeladenker.com

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

Two Truths for a Post-Pandemic Church

Has this ever happened to you; there is a TV show you love to stream and either you get distracted between seasons or there are some production delays, so a significant amount of time has passed between watching the last season and the newest season? There is so much excitement when you begin watching the new season as you recall how great the last season was. Then you start watching the show and somehow, it’s different from what you remembered. Maybe your favorite character has left, maybe the storyline hasn’t changed or changed too much, maybe you overly romanticized the show and now you’re disappointed. Or maybe you are in a different place in life, and you relate to the characters a little less.

You know what’s funny, in some ways this is how people are experiencing their return to living life in public, more specifically, this is how we’re experiencing our return to an in-person Christian community. As a leader in a community, it would be easy to assume that each member “returning” to our sanctuary is ready to rock and roll picking things up where we left them at the end of season three. But this is one of those seasons that opens with “three years later” and we have to spend the first half of the new season catching up.

We will be doing ourselves a disservice to believe that everything is the same, can be the same, or should be the same as it was before the pandemic. I know a lot of community members and leaders are wondering what ministries will look like as guidelines change and vaccines continue to roll out. I am a firm believer that each ministry’s answer to this question will be and should be different. But as we move into the next season of our ministries here are two things I’m thinking about:

We cannot pretend everything and everyone is the same.

This last Sunday, I connected with a family I hadn’t seen in a while. We’ve connected on Facebook, we’ve emailed about some service projects, and the ministries their kids are a part of. Although we have stayed connected in these ways, they have not been physically in worship for fourteen months. Fourteen months. As we chatted I started to really notice the people walking through the sanctuary doors. Then it hit me, while I have known these people for some time a lot may have happened since I last saw them. It would be silly to assume that after a year and a half that anyone would be fully the same person they were before and therefore why would we assume our community is the same? Have you ever thought about how much can happen in one's life after so many months? In some ways as our communities return in-person, we are creating a whole new community. It’s almost like you’re joining a new church or taking a new call; the first phase is getting to know the community.

As we begin to gather again and see some people for the first time in a while, let’s not assume we know this version of each other. Our experiences over the last several months have influenced how we see and experience life. Our experiences of grief, loneliness, isolation, loss, and rage have shaped us. Just as our experiences of joy, new life, love, accomplishment, and healing have changed us. I think one of the best investments we can make right now is in getting to know our community once again. There is no need to assume, instead let’s hold a posture of curiosity and a desire to know one another.

Take a moment to focus and be grounded in a fundamental truth.

As we enter a new era in our ministries, we will need to hold in tension our desire to do everything and our true mission (whatever that is for your community). I already see communities reaching for all the things that sound fun, trying to make up for lost events and experiences. I am deeply hopeful as things continue to evolve in a positive direction for my community, but I don’t want to romanticize the idea of community so much that we do not love or lead our people well.

I want to encourage you as well to take a moment to focus and get grounded in your mission and values so that when the desire to guide people into returning to church arises, you will have something firm to stand on. As I sit in meetings about sermon series, worship plans, and community outreach opportunities, I’m trying to remember how these ideas fit into a large narrative both missionally and biblically. So if the question we’re pondering is, what does post-pandemic community look like? I argue to start with your mission and theological framework. What is your understanding of community? How is that different and similar to Christian community? What purpose does community serve in our ministries? Is it to get people committed to the church you lead? Is it to be a gateway to dollars and keeping the church alive? Sometimes our actions make it seem like the latter are our true desires.

When I think of the Christian community I hope for, it’s one of transformation, redemption, and reconciliation. A community that reminds each other of who we are in Christ and how we are loved when we forget our value. A place that seeks justice, liberation, and serves beyond itself. This isn’t a thought experiment for one, but for all, every leader and member can benefit from a moment to reset and reframe our work as move forward.

One final thought, and listen close, I’m going to tell you something you may already know but you might need to hear anyway. This is not a competition. This is not a race. There is not a trophy to be won here. We are too diverse, and our needs are too great to be in a competition mindset. Lean into one another's strengths and strive to love your community the best way that you can.

Jessica Gulseth

Jess Gulseth is a seminarian at Luther Seminary in St. Paul seeking ordination in the ELCA. Jess is a Director of Children & Family ministry in the Des Moines, IA area.

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

Searching for Why

In her book 2018 The Great Convergence, Phyllis Tickle said "every 500 years the holy spirit has a rummage sale." Tickle made the argument that we were in a new reformation in the history of the church and challenged us to think about what things the spirit might be putting a price tag on this time around.

How I long for the wisdom of Tickle today as we emerge from a year and a half of challenges to our faith and the various structures that contain it.

It really feels like we're right in the middle of another reformation.

The pandemic has caused many of us, myself included, to ask a lot of questions about the church.

What does it mean to be the church?

What does it mean to gather?

Do buildings matter?

What does it mean to be incarnational, and can we be incarnational on different screens?

What does our faith have to say during a time of communal trauma like a global pandemic?

Right in the midst of asking some of these questions, I joined a small group of creatives working through Julia Cameron's "The Artist's Way." One of the key components of Cameron's work is challenging artists to consider why we create. Is it possible, she asked, to create for nothing else but the sake of creating? Not for followers or publishing or notoriety or fame or fortune, but simply because you are meant to create?

Add this to the question from Phyllis Tickle, and then also add the recent slew of lectionary texts from Acts and you have a recipe for a stirring pot inside of me.

We are, in the church, very, very good at asking "what" and "how" questions.

What can we do to get more people here?

How can we encourage people to attend this program or give more money?

What new thing do we need to do?

How can we attract visitors?

What how what how.

None of these tell anyone anything about what we believe. They don't answer the why.

Why do we have church?

Why do we follow Jesus?

Why does this matter?

Can we worship simply for the sake of worshipping?

Can we follow Jesus simply for the sake of following Jesus?

Would that change anything we do and how we do it?

I think so. I think right now the Spirit is asking us to search for our why. And she is putting price tags on everything that is a "what" and a "how." Those things matter less.

In a 2009 TED Talk, Simon Sinek said that "what you do simply serves as the proof of what you believe." To that I'd add, what you do and even how you do it simply serves as the proof of what you believe.

You have to search for your why.

Our lectionary texts since Easter have placed us again in Acts. But I wonder if this year we can hear these familiar stories of the early church as not a blueprint but what happens when we really solidify our why.

When the why is following Jesus, then what happens is Acts 4. We love radically, seek justice, tear down systems of oppression and exclusion. And the church grows as a result.

When the why is following Jesus, then what happens is Acts 8. When the Ethiopian Eunuch asks Phillip, the church insider, "what is to prevent me from being baptized?" Phillip could have said any number of things: "You haven't taken a baptism class yet," "you need to be taught the right way to do things," "you aren't Jewish," "you aren't one of us," etc. But instead the answer was nothing. There was nothing to prevent anyone from being baptized. Phillip got out of his own way and let the spirit do her work.

The church grew as a result.

On Pentecost we celebrate the Spirit coming in and blowing the doors open and removing all barriers and getting to work.

There is no controlling her, no setting boundaries or making sure it's done the right way.

The spirit is at work in our churches right now and things are scary and unfamiliar and we are being asked to move into a place we can't imagine. Our tendency is to find safety and control in the how and what questions:

What program can we start?

What kind of music should we have in worship?

How can we make more money?

How can we bring in more people?

But I believe that these are the wrong questions.

Why do we gather?

Why do we follow Jesus?

Why does this matter here and now?

So that's what I think these next few months are going to be about — our why.

Meta Herrick Carlson was a guest on my podcast Cafeteria Christian this past week, and in our conversation she reminded us that we have all changed, but the systems we are in have not caught up yet. These systems are going to do their best to move us back. Back to where we were, back to what is familiar, back to the way we've always done it.

The church can be one of these stuck systems, prioritizing it's own survival over the call to follow Jesus. Moving away from what is to come in favor of what was and what used to be.

But the spirit isn't asking us to do that. The spirit is calling us forward. Into something new.

I wonder if we have the imagination to clear our minds of the what and the how and search for our why?

And when we can articulate and believe in our why, can we then let the spirit dictate the how and the what and can we hear what she is saying in the rushing wind and refining fire?

Can we let her move us into what is next?

It will be, God declares,

that I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh,

and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy,

and your young shall see visions,

and your old shall dream dreams. (Acts 2:17)

Natalia Terfa

Natalia is a Lutheran pastor and author who lives in Minneapolis with her hubby, kiddo, and kitty babies. She loves to bake, to read, practice yoga, and find nature adventures. She is passionate about the church of the future, one with no boundaries and filled to the brim with love and grace and laughter and snark and a lot of fellow “not that kind of Christians.”

Natalia co-hosts Cafeteria Christian, a podcast for people who love Jesus but aren’t so sure about his followers.

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

Real Christian Talk about Israel and the Palestinians

It’s tempting to grow weary of the cycle of violence in Israel and the Palestine. Hamas attacks Israelis, usually civilians, and Israel responds with overwhelming force. A cease-fire holds this Friday after a horrid week. Already the Palestinian death toll has exceeded 250, including 62 children, with a dozen Israelis dead. And the devastation in Gaza exceeds the death toll.

It’s easy to grow weary because the cycle keeps repeating itself from decade to decade — and because we don’t understand the conflict well enough. The loudest Christian voices tell us we should support Israel no matter what. Other loud voices tell us that any criticism of Israel and its policies amounts to antisemitism. The news media misleads as much as it helps. Its policy of neutrality obscures the scale and nature of the violence. Sources like the New York Times describe a “conflict,” “Israeli-Palestinian Strife,” and “fighting” even when describing Palestinian kids throwing rocks at Israeli soldiers who fire automatic weapons. An impressive new study by MIT undergraduate student Holly M. Jackson shows the media is far more likely to apply violent language to Palestinians than to Israelis. We can all decry Hamas’ terrorist tactic of firing rockets into Israeli neighborhoods. We should. But Monday night and Tuesday morning, 62 Israel fighter jets attacked targets in Gaza with 110 “guided armaments,” also known as smart bombs.

The conflict is not symmetrical. News coverage is not symmetrical.

Nor is the reality on the ground. Whenever it wants, Israel makes life impossible for ordinary Palestinians. It can turn a three mile commute into a three hour ordeal. It can destroy olive orchards that take a decade to reestablish. It can cut off the supply to food and medicine. Israeli settlers violate treaties and take over Palestinian neighborhoods. Israel holds most of the power, leaving the Palestinians in what former president Jimmy Carter famously described as an “apartheid” situation, “total domination and oppression of Palestinians by the dominant Israeli military.”

We Christians recognize our faith’s roots in biblical Israel and in Judaism. We also confess Christianity’s long and brutal history of antisemitic violence.

The state of Israel represents an effort to establish a homeland for Jews in the wake of the Holocaust, a nation safe and free. For reasons of both faith and human rights, Christians have good reason to support an Israel that lives in peace and security.

That baseline commitment does not preclude criticism of Israel when its policies are unjust. The current wave of violence follows significant Israeli provocations: a court ruling that removed Palestinians from their homes so that Israeli settlers could displace them, followed by an incursion of Israeli police into the Al-Aqsa mosque during Ramadan that led to Palestinians throwing rocks and Israelis firing rubber bullets and stun grenades.

Some Christian preachers will tell us that Christians should support Israel regardless of its policies. Citing biblical passages that proclaim God’s love and loyalty to Israel, they blur the Israel of the Bible with the modern secular state of Israel. They also forget that the biblical God judges all nations, including Israel, with equity. Modern Christians have every good reason to support the Israeli state. But support does not exclude accountability.

We should also recognize how profoundly the Christian Right’s teaching regarding Israel is shaped by a perverted end-times scenario. Prominent pastors Robert Jeffress and John Hagee participated in the dedication of the new United States embassy in Jerusalem. Both preachers are end-time prophets who declare that Israel must exist in order for Jesus to return. Jeffress preaches that Jews who do not embrace Jesus will go to hell, while Hagee preaches that all Jews will convert to Christianity upon Jesus’s return. Although they claim to love Israel, it is no more than a prop in their perverse end-time fantasies.

Others will accuse anyone who criticizes Israel as being antisemitic. We should not fear them. Israeli public opinion is heavily divided on how Israel should relate to the Palestinians. Israeli activists join the majority of global opinion in decrying the illegal occupation of Palestinian lands. So is opinion among American Jews. As The Forward editor Judi Rudoren wrote this week, “We can support Israel’s right to exist and criticize its government’s treatment of Palestinians — just like we believe in the United States but might think the way it treats immigrants or poor people is unfair.”

The 1967 Six-Day War set up the fundamental conditions that led to Palestinian oppression. Israeli forces defeated those of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. After the war Israel occupied the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and the Golan Heights to provide a buffer zone. Although the United Nations has called on Israel to withdraw from these occupied territories, about six million Palestinians yet live under Israeli domination. Their own formal government is subject to dysfunction and cannot defend them from Israeli actions.

It is possible to think several things at once. We should condemn Hamas for using terrorist methods to intensify conflict, even as we condemn Israel for oppressing Palestinian people and occupying their territory. We can value Israel’s right to exist and protect itself without extending a moral blank check. We can value Israel’s national integrity and work for a free and safe Palestinian state. As Christians, we can honor our Jewish heritage and value the Jewish people without smashing our moral compass.

Despite the media’s efforts to promote over-simplified narratives, it’s possible for us to hold multiple truths in tension with one another. Let us not grow weary in our insistence upon justice for the Palestinians.

Resources:

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and United Church of Christ declarations.

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America: “A Social Message on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” (1989)

Presbyterian Church (USA): “Resolution on Israel and Palestine: End the Occupation Now.” (2003)

United Church of Christ: resolutions, 1967-2019.

United Methodist Church: “Opposition to Israeli Settlements in Palestinian Land.” (2016)

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops: statements related to “a just peace between Israelis and Palestinians.”

Greg Carey

Greg Carey is Professor of New Testament at Lancaster Theological Seminary and an active layperson in the United Church of Christ. His books include studies of apocalyptic literature, the parables, the Gospel of Luke, and the ethics of biblical interpretation. His most recent books are Stories Jesus Told: How to Read a Parable and Using Our Outside Voice: Public Biblical Interpretation. In addition to serving on multiple editorial boards, Greg chairs the Professional Conduct Committee of the Society of Biblical Literature and serves on the Leadership Team of the Open and Affirming Coalition of the United Church of Christ.

Facebook | @gregc666

Twitter | @Greg_Carey

Facebook | @LancasterTheologicalSeminary

Twitter | @LancSem

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

Thriving Beyond Covid: Crisis or Opportunity?

Who could have imagined that a microscopic virus named Covid-19 would cause so much disruption in our world, our lives, and our churches? Weariness, grief, uncertainty, and even division have become viral as we struggle to recover. The long-term impact of Covid on congregations remains uncertain, but I am convinced that the attitude and spirit of church leaders and members as they respond to this crisis will play a key role as they navigate the challenges ahead.

In two of its definitions for “crisis,” the Merriam-Webster dictionary connects crisis with opportunity: the turning point for better or worse and the defining moment. The Chinese characters for “crisis” capture this connection as well: Danger and Opportunity. Albert Einstein saw the connection too: “In the midst of every crisis, lies great opportunity.”

It’s all about getting people in the right frame of mind to see beyond this crisis to an unprecedented opportunity to move from death to resurrection in the church. It’s time to begin an exciting Spirit-powered journey to trust God to empower your dreams and to rise up to embrace opportunities.

Prior to 2020, congregational vitality statistics were already grim. For the past 20 years, research has reported that 80-90 percent of the churches in the U.S. were either plateaued or declining. 3,500 to 4,000 congregations were closing every year. That’s approximately 10 per day. David Kinnaman, president of the Barna Group, a faith-based research organization, recently reported that as many as 1 in 5 U.S. congregations could close their doors permanently as a result of Covid. Many more may struggle to stay off life-support.

None of us want that to happen but all of us need to a plan to avoid it.

In reality, most congregations have been facing a sustainability crisis for decades. A pre-Covid study of chronic decline in average weekly worship attendance in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) projected that if the current rate of decline is not turned around, the total average weekly worship attendance in the ELCA will plummet from 899,000 people in 2017 to a dismal 15,811 in 2041! And that number does not factor in the impact of Covid.

The damaging by-product of church decline has been a steady rise in the levels of fear and worry present in our congregations regarding their future. The toxic fruit of fear and worry is doubt, which undermines the power of faith needed to move mountains. Fear, worry, and doubt were at high levels in most congregations prior to Covid. They have gone viral now, rising to dangerous pandemic levels in many places. These negative emotions must be acknowledged and dealt with in whatever re-gathering / renewal plan congregations make.

When Peter got out of the boat and began sinking, he cried out to Jesus for help. It would be wise for us to do same and to listen to his advice. There was a reason he told his followers 24 times in the Gospels to not be afraid, worried, or filled with doubt: When these emotions invade our corporate spirit, they eat away at a congregation’s vitality and hinder its ability to thrive.

Fear, worry, and doubt can deflate the corporate spirit, derailing dreams, and diminishing impact. If they become the dominant spirit in a congregation, they undermine the faith, optimism and hope that sustains it.

When faith takes a back seat to fear, the focus shifts to our diminishing resources and our mission is compromised.

Addressing these mostly unspoken emotions is the often overlooked first step on the path to congregational renewal in any season, but especially now. To ensure that you turn this crisis into an opportunity, releasing these negative emotions must be a desired outcome in whatever re-gathering or renewal process your congregation undertakes.

The treatment for this is simple: expose members’ fears, worries, and doubts to the light by creating opportunities for people to share them with one another and with God. When you do this you undermine and reduce their power, removing a key point of leverage the powers of evil love to use to meddle in God’s mission.

Once this step is taken, these negative emotions can be removed from your corporate spirit so that God’s Spirit becomes the driving force that awakens and empowers dreams, helps you overcome your challenges, and embrace new opportunities.

By sharing with others you discover that you do not walk alone and are encouraged. By being vulnerable with God you open the door for God’s power to take over so that these emotions do not hold you back and undermine your re-gathering / renewal efforts. It’s time to let go of the burdens and embrace the future. God wants to empower you to live by faith and trust the Spirit to empower your dreams.

To facilitate this journey in congregations, I have developed a free multi-session scripture based re-gathering / renewal resource called Thriving Beyond Covid to not just keep your congregation from closing or struggling to stay off life-support, but to help you turn this crisis into an opportunity to thrive.

In this season, embrace and believe Paul’s witness in Romans 8:28 that God makes all things work together for good and in Ephesians 3:20 that by the power at work within us, God is able to accomplish abundantly far more than all we can ask or imagine.

We can’t move back to the church we used to be. Move forward to the Church God is calling you to become.

Pastor Jeff Linman

Thriving Beyond COVID was developed as a gift to the church by Pastor Jeff Linman. Jeff has a passion for awakening Kingdom impacting dreams in the church. In 33 years as a pastor, he served 4 congregations, 20 of them as the founding and lead pastor of Spirit of Joy Lutheran Church in Orlando, Florida. Jeff is originally from Monmouth, Illinois and iis a graduate of Florida State University and Luther Seminary. He currently lives with his wife Patti in the mountains of western North Carolina. They have two children, Josh, currently redeveloping a congregation in Decatur, GA and Sarah, a social worker in Atlanta, GA.

Jeff has also launched two other church renewal initiatives:

Ignite the Church Conference

Dream Leader's Initiative, a congregational renewal and coaching ministry.

Imagining Christian Community Post-Pandemic

Church Anew is dedicated to igniting faithful imagination and sustaining inspired innovation by offering transformative learning opportunities for church leaders and faithful people.

As an ecumenical and inclusive ministry of St. Andrew Lutheran Church, the content of each Church Anew blog represents the voice of the individual writer and does not necessarily reflect the position of Church Anew or St. Andrew Lutheran Church on any specific topic.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The CDC’s announcement that vaccinated people no longer have to wear masks, whether indoors or outdoors, stirred all kinds of reactions. Victory for some. A sense that at long last, this long nightmare was starting to draw to a close in a significant — if still incomplete — way. For others, the news was not all that welcome. What about those of us with children who are not yet eligible to be vaccinated? What about those in our communities who are immunocompromised? For some, therefore, the announcement was not a prompt to celebrate but to wonder whether we are moving far too fast.

I am not writing this to mitigate between those reactions. I am not a public health expert nor am I a psychologist who might help us understand the way the last year has affected us all in ways visible and not.

I do see an opportunity to encounter this moment of transition, this moment of long-awaited but fear-inducing change.

I see an opportunity to name in preaching the traumas our communities have endured, the scars we still carry, the hopes we cannot yet articulate. I see an opportunity to invite us all to a generosity and love of our neighbors that reflects the abundance of God’s own grace.

In its yearly journey though the Book of Acts in the season after Easter, the lectionary takes us to the beginning of a story about the followers of Jesus wresting with what comes next. Having witnessed their friend denied justice and brutally executed by an empire which cared only for the propagation of its power, two disciples then encountered him in the flesh on the road to Emmaus. That same resurrected Jesus ate with them even as the disciples were “startled and terrified” (Luke 24:37). As Acts begins, this same Jesus commissions his followers to be witnesses of the good news “…to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8), calls them to wait in Jerusalem (1:4), and then ascends into the heavens.

“What now?,” they must have wondered. “What’s next? Where do we go? What do we do? What’s the first step? When do we get going?”

Starting in Acts 1:15, one answer is given. First, seemingly, the community needed to come face-to-face with a trauma not yet addressed in the narrative. In the passage, the community remembers the betrayal of Judas and his terrible demise. One who had walked among them as a follower of Jesus had betrayed both him and the community. Judas had shared meals with his fellow disciples and Jesus alike, had walked with his fellow disciples and Jesus alike, had hoped and prayed alongside his fellow disciples and Jesus.

So, what does the community do in this moment? Peter turns to the Scriptures for imagination and guidance, not so much an explanation for Judas’s betrayal but a sense of what moving forward might be like. And then the community forwards two witnesses whose qualifications are relatively straight-forward: they were there. They saw Jesus heal. They heard him preach. They suffered as he died on an instrument of imperial injustice. They were “startled and terrified” at his resurrection. I wonder if these two witnesses weren’t quite sure what to do next, what would come next. Perhaps, being a witness of Jesus’s gospel does not require that kind of certainty.

And notice that the community does not vote or invite Peter to make the choice between these two witnesses. They cast lots. Why? Not to leave the decision to chance but to invite God’s hand to lead the community.

Acts is not a blueprint for building a perfect community. So also, this scene does not provide easy instructions for how we move in and through the multiple traumas of this last season of our lives. But I wonder what imagination might emerge for us in this story?

I wonder what’s not said in this story. What about those in the community who still missed Judas, their friend? What of those who saw his betrayal as a failing not of the individual but of a community? What about those who were not ready to move on from Judas’s betrayal, who wanted to keep the eleven as a group rather than reconstitute the twelve so that Judas’s absence would be a constant reminder of his betrayal or a persistent warning to others who might do likewise? And what about those who had seen the resurrected Jesus, heard his call to witness to the ends of the earth, but weren’t quite sure they were ready to believe, who still hurt too much to imagine a different future beyond the trauma of loss and betrayal?

So, what comes next for us now?

As COVID numbers plunge here in many parts of the United States, they soar in India. As some in our congregations welcome a new day, others wonder if that new day includes them or even if that new day has yet dawned. So again, what comes next? This little story in Acts might suggest that what comes next is not a smooth, easy, clearly discernible path or instant healing from what we have endured.

What comes next is a call to witness and a promise that God has always walked with us.